Starting School: A Guide for Parents and Carers

Starting school is a big milestone that marks the beginning of a new chapter for children, their families and caregivers. From fun-filled orientations to shopping for supplies and getting dressed for the first day, the lead-up to school is a time of excitement and uncertainty, so it’s natural for everyone to feel a bit anxious.

This guide, thoughtfully crafted by our team of experienced child psychologists and occupational therapists, will help you navigate the path to school no matter how bumpy it might be. It offers tips and strategies for managing emotions, building connections and shaping a joyful and enriching start to their school years.

BEFORE SCHOOL STARTS

Begin with the foundations

More than anything, connection-building and reassurance are important. Stepping bravely into a new adventure can be overwhelming for kids (and adults), so providing a steady stream of support and understanding can make a difference.

When the world feels big and scary, words of reassurance and a tight hug can help your child feel safe and seen. Let them know it’s normal to be nervous about new experiences and that they’re not alone. You might like to share your story of starting school or talk about their friends who feel the same way. Either way, focus on the things you know they might enjoy, like making new friends, learning new things or a particular activity like art.

Wherever possible, involve your child in the process of getting prepared for school. This gives them a chance to make small decisions and have a sense of ownership during the transition. Being involved and learning the ropes can also reduce the stress of busy days.

Get familiar with the school

Separation is hard for parents and kids, especially in a new environment that you’re both unfamiliar with. A simple way to help your child adjust to school and ease any separation anxiety you might both feel is to explore the school environment together.

Take a drive to the school during a holiday or weekend, spend some fun time on the playground, and walk them through where you’ll drop off and pick up each day. Just as a warm hug and comforting words can alleviate their worries, this familiarity can build their confidence and comfort in a new setting.

Use social storytelling

As parents, we want to trust that our children will be safe and capable in their new school environment. This trust can significantly reduce our stress, allowing us to support their transition more confidently and positively.

Creating and reading social stories is a great way to help your child learn about the school, get familiar with the setting, understand things they might do each day and get to know the faces of the principal and teachers. Some schools include social narratives in their welcome pack, but you can also create your own social story using a template.

Is your child a bookworm? When reading together, include stories about starting school. Talk about the characters, their emotions, and their adventures to help your child connect with the experience.

Visual aids like a countdown calendar can also be fun and informative.

Practise your new routine

Like social stories, practising your new school routine can help your child feel more prepared and less overwhelmed when the school bell finally rings.

If your mornings need to start earlier than usual, make the change a couple of weeks before the school term begins. Try to build more structure into your days to mimic the activity-play-activity rhythm of school.

If your child has a new lunch box, get it out and use it during the holidays. Simple things like packing, zipping and emptying their lunchbox can build confidence. Encourage them to try on their school uniform so they know what it feels like and to ensure it fits.

Be mindful of your language

The language you choose can play a role in shaping your child’s feelings about starting school. Instead of marking this transition with finality, such as saying “This is your last day at daycare,” try to use more positive language. Use phrases like “We’re saying goodbye to daycare to get ready for our new adventure at school!” This approach frames starting school as the beginning of something new and exciting.

Normalise feelings of anxiety and worry. Try saying things like “Starting school can make you feel worried or scared, but I’ll be here for you. I’ll drop you off in the morning and come back in the afternoon like I always did at daycare.”

Lean on helpful resources

If you’re feeling anxious or overwhelmed as a parent, remember it’s okay to seek assistance. Turning to resources and support during these times helps you and models an essential skill for your child. It teaches them that there are steps we can take in moments of uncertainty and people who can help.

Heading off to school is a big change for your child, but it’s also a significant change for you. Keep in mind that emotions are contagious and can easily transfer from parent to child, so the better prepared you are to manage your anxiety, the more equipped you’ll be to support them as they settle into school.

THE FIRST FEW WEEKS

Slow down and connect

Aim to slow down and enjoy time together in the days leading up to school. This could mean having breakfast together, reading a book or simply enjoying a quiet moment before the day begins.

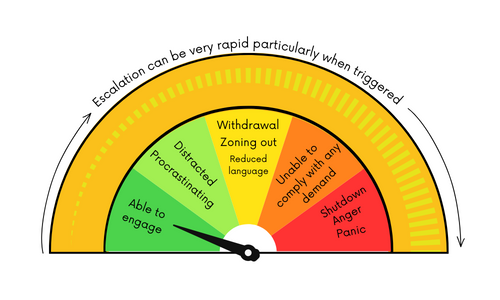

Be prepared to support your child through a mix of emotions. While some kids transition easier than others, it’s common for them to show lots of big feelings in the lead-up to school that aren’t always related to school. They might feel overwhelmed and emotional, clingy, and generally respond differently than usual.

So, be ready to offer support in the way that best suits them, whether that’s through conversation, quiet time, or a comforting hug.

Balance activities with rest

Consider reducing household chores and adjusting your child’s extracurricular schedule to allow for more downtime. The excitement of starting school, along with the increased cognitive load, is likely to make them feel more tired and potentially stressed. Our guide to spotting stress in your child can help you notice behavioural and emotional changes that might signal the need for extra rest.

Do they have a favourite activity, like swimming or dancing? Keeping it as a part of their regular routine during this transition can be helpful. However, if there’s an activity they’re not as fond of, now might be a good time to take a break from it.

Allow space to process

After school, allow your child the time and space they need to unwind. Some children might want to talk about their day right away, while others might need quiet time or physical activity to relax. Understand and respect their individual needs for processing their day.

Support their unique needs

If your child is neurodivergent or finding the transition particularly challenging, don’t hesitate to seek extra support. This could involve scheduling additional appointments with your healthcare team or discussing specific needs and support strategies with the school.

Celebrate milestones

Finally, marking the end of the first week with a special activity can be a wonderful way to celebrate this new chapter. Whether it’s a favorite family dinner or a treat like ice cream, it’s a great way to acknowledge their accomplishment and the start of their school journey.

Step by step together

As your child takes their first steps into their school life, hold their hand with love and assurance, knowing that you’re doing a great job. Remember, each child is unique, so adapt these tips to fit your family’s needs and dynamics. Here’s to a successful and joyful start to school life.

Dr Nicole Carvill is an accomplished child psychologist, researcher, presenter and PhD graduate who dedicates her time to helping children and families thrive. A mother of two and caregiver by nature, she approaches therapeutic support through the lens of a psychologist with the heart of a parent.