Pathological Demand Avoidance: A Guide for Parents and Carers

Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) is a behavioural profile on the autism spectrum, marked by an intense need to avoid everyday demands. Children with PDA aren’t being difficult – they’re responding to deep, persistent anxiety that makes them feel unsafe.

With high anxiety in the driver’s seat, everyday tasks can overwhelm these deeply feeling kids, triggering big emotions and reactions that are hard to manage without the right support.

If you’re a parent, carer or educator who’s navigating these moments or feeling unsure, this guide is for you. At Think Psychologists, we walk alongside many families experiencing PDA, and we know that compassionate, tailored support truly makes a difference.

What does PDA look like?

For children with PDA, everyday life can feel like a constant battle between fight, flight, and freeze. Their anxiety is often intense and difficult to shake, driving a strong need to avoid situations they can’t control.

On the outside, you might see humour, distraction, arguing, or a need to take control. But inside, their brain is constantly assessing, questioning, and scanning for threats. Over time, this mental overload can become too much, leading to shutdown.

What looks like refusal is often something else entirely: a child navigating an overwhelming world in the only way they know how. It’s not defiance – it’s a survival response.

At its core, PDA is a neurological power struggle between the

DR NICOLE CARVILL

brain, body and heart.

With PDA at play, social settings, communication and friendships can become tricky, and children need lots of support to manage their emotions.

Every child with PDA is different, but there are some common patterns we often see:

- An obsessive need to be in control

- Avoiding participation, even in activities they usually enjoy

- Difficulty socialising or understanding boundaries

- Big mood shifts, including meltdowns or shutdowns

- Speaking and acting beyond their age, using adult-like language

- Using humour or distraction to steer away from tasks

- Immersing themselves in fantasy or intense roleplay

Children with PDA often want to meet expectations, but their nervous system shifts into high alert and applies the brakes the moment something feels too big, too fast, or out of their control.

Living with PDA can be challenging, but in my experience, these children also show remarkable creativity, humour, and determination – qualities that grow into real strengths over time. They’re usually also deeply charismatic and wonderfully tenacious.

"PDA is like trying to face your phobias every waking moment!"

– Riko, Riko’s blog.

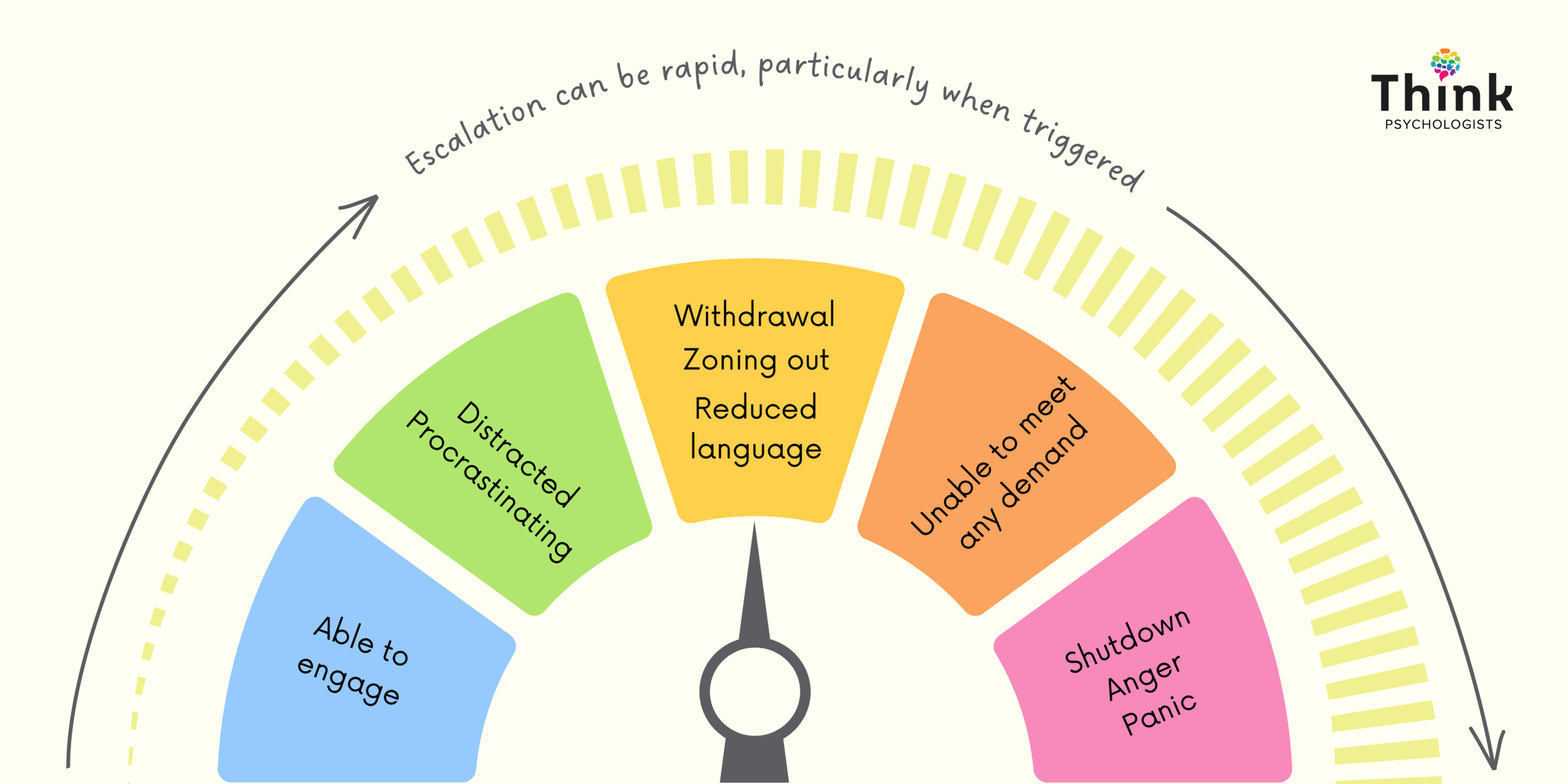

The PDA scale of distress

PDA-related anxiety builds in layers, often without warning. One moment, your child seems fine, then the next they’re overwhelmed.

The PDA Scale of Distress begins in a state of calm, escalating to complete shutdown as demands, expectations and anxiety increase.

© 2025 Think Psychologists: PDA Scale of Distress. All rights reserved.

- Blue and green zones: Your child is calm but still finding subtle ways to avoid demands (like dawdling or changing the subject).

- Yellow zone: They become withdrawn, less talkative, and less able to take in instructions.

- Orange zone: Demands feel completely unmanageable. Your child may freeze, panic, or become verbally resistant.

- Red/pink zone: This is full shutdown or meltdown. Fight, flight or freeze kicks in and regulation is almost impossible without support.

When distraction, control and avoidance strategies fail, anxiety levels skyrocket, and distress escalates. Adults with PDA sometimes liken this feeling to a panic attack.

PDA and school avoidance

From pre-school through to high school, PDA can show up as what’s often called “school can’t.”

School, with all its rules and regulations, tends to be a tough environment for these kids. Getting out the door becomes a battle. Uniforms feel unbearable. Instructions become landmines, especially if they don’t really interest you.

For some kids, this daily stress is intensified by Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (RSD) – an extreme emotional response to perceived criticism, failure, or social exclusion. In a school setting, being corrected by a teacher or left out by peers can trigger RSD, compounding the anxiety already present with PDA.

In Australia, PDA isn’t yet a formal diagnosis under the DSM-5. But experienced, PDA-aware clinicians can identify a PDA profile during (or after) an autism assessment.

For many parents (and educators), it feels like you’re constantly firefighting, without a clear plan. If this sounds familiar, our article on navigating school avoidance might be a helpful.

How is PDA assessed?

The testing process is collaborative and involves key caregivers in a child’s life, including parents, educators and other relevant professionals. The process can vary between clinics, but usually includes the following steps:

Step one is a parent-only appointment to:

Step two is a face-to-face appointment with your child focused on:

- explore your child’s developmental history and skills

- discuss particular concerns and talk openly about challenges

- complete a take-home parent/carer questionnaire

- building a relationship and trust

- exploring PDA characteristics through conversation, games and activities that interest them

- using non-directive language to introduce ideas

In this session, we will also explore potential sensory stressors which can assist with profiling and support. Parents are welcome at face-to-face appointments.

Step three involves seeking feedback from educators and other professionals familiar with your child to explore how they present in a range of environments.

Step four will determine a PDA profile, if appropriate.

Armed with the above information, your child psychologist will apply clinical judgement to diagnose a PDA profile. Younger children who are still developing or don’t fulfil all profile criteria can be diagnosed “at high risk” of PDA.

The testing process can take several weeks and seem daunting at first. Despite this, parents are often relieved by the outcome, as it gives them a better understanding of their child’s needs and a framework for moving forward.

As more families seek answers, clinicians are seeing a clear pattern: many of the children facing the biggest challenges are those with undiagnosed (or misdiagnosed ) PDA. Early identification, even without a formal label, can make a lasting difference.

Not sure if a PDA assessment is right for your child? Booking a one-off consultation through our Parent Support Program can help you talk it through and decide what’s right for your family.

How common is PDA?

Autism itself affects about 1 in 40 Australians, and as awareness grows, so too does recognition of more nuanced profiles like Pathological Demand Avoidance.

PDA isn’t a formal diagnosis in global diagnostic manuals, but it’s increasingly recognised by healthcare professionals as a meaningful part of the autism spectrum. In Australia, this change is reflected in the National Guideline for Autism Diagnosis, which now includes PDA as a behavioural profile.

Not every child on the autism spectrum shows PDA traits, but research suggests that around 1 in 5 do, and approximately 4% (1 in 25) meet the full profile criteria. While these traits may soften with age, many families still face daily challenges that call for thoughtful, individualised support.

Why PDA is often misdiagnosed

Because PDA isn’t a standalone diagnosis, it’s often confused with Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD).

The difference? PDA is rooted in anxiety, not defiance – and it tends to shift and evolve depending on context, which can make it harder to identify.

When PDA is misunderstood or misidentified as ODD, traditional strategies can increase distress rather than ease it.

A psychologist familiar with the PDA profile can help you untangle these nuances and create a more accurate picture of what your child is experiencing.

Practical support strategies for PDA kids

If your child is identified as having a PDA profile, it’s important to remember that you don’t have to navigate this new path alone.

For some parents, the path to effective support begins with a mindset shift. Recognising that your child’s behaviour is driven by anxiety—rather than being intentional—opens the door to better communication and more proactive support. From there, the focus is on helping your child feel more in control of their anxiety, because that’s at the heart of what can make things easier.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to PDA care. Often the strategies we lean on for children with autism can make things worse for children with PDA. Plus, what works well for one child may not work for another, and the effectiveness of strategies can shift over time.

Shift to low-demand language

A good (and often effective) starting point is changing how we communicate. Reframing demands using playful or low-demand language reduces pressure and invites collaboration. It helps your child feel more in control, without abandoning the task at hand.

For example:

- Instead of “It’s time to put your shoes on,” try “I’m putting my shoes on now.”

- Instead of “You need to brush your teeth,” try “Shall we go pick a toothbrush?”

Low-demand language is particularly helpful with PDA but can also support children of all ages and stages.

Invite flexibility and fun

In addition to shifting your language, these gentle strategies can help reduce pressure and support your PDA child to feel more safe and in control:

- Allow extra time for tasks (and ditch the timers)

- Use humour or novelty when your child is open to it

- Offer choices rather than ultimatums

- Focus on connection before redirection

- Gently prepare your child for new situations with visuals or stories

- Take breaks when needed – even if that means stepping away

We know this one’s easier said than done, especially when you’re running on empty – but staying steady and consistent can help your child feel more secure and less alone in their big emotions.

Most importantly, be flexible and collaborative when it comes to tasks and expectations.

And if things don’t go as expected? Try not to take it personally. Kids with PDA can sometimes say things that sting, but it’s usually their anxiety talking, not their true feelings. Reframing helps you see these moments for what they are: signs that your child is overwhelmed, not trying to hurt you.

Supporting PDA in the classroom

Keep in mind that building a relationship with a child who has PDA can take time. The child likely has a history of challenging interactions with authority figures, so it’s important to establish trust before working on strategies.

Interested in learning more about how to support children with a PDA profile? Our Educator Support Program can help you on this journey.

Medication and tools for PDA

Medication to alleviate anxiety can be helpful for some children with PDA. Introducing medication is a personal choice and one you can explore in collaboration with your child’s psychologist and paediatrician.

Supporting siblings of children with PDA

When one child needs a lot of attention and support, siblings can sometimes feel overlooked – even if they don’t say it out loud.

We encourage families to look out for small signs of stress in siblings, like withdrawal, hypervigilance or changes in mood. These subtle shifts can point to emotional overload.

“Siblings are often highly skilled at pushing down their own feelings. Look for the micro behaviours: more quiet than usual, glassy eyes, or being easily startled.”

– Dr Nicole Carvill

Explore practical ways to nurture every child in your family with our guide to supporting siblings of neurodivergent children.

Support starts with understanding

PDA can feel overwhelming, but you don’t have to navigate it alone. Every family’s journey is different, and we’re here to help you understand your child’s needs and find a path forward you – starting with a simple, supportive conversation.

Further learning

Here are some valuable resources to support deeper understanding of PDA. Whether you’re looking to shift your language, adjust expectations, or better understand a child’s experience, this collection is designed to help.

🌐 Articles

- Navigating PDA and School Avoidance: How to Support Children and Families

- How low-demand language can support children with PDA (and sensitive kids too)

- Autism, PDA and RSD: Understanding the connection

- Autism Awareness Centre – Low Demand Parenting

- Pathological Demand Avoidance Australia & New Zealand

👆 Downloads

- Daily Demands Checklist Bundle: A practical download designed to help parents, educators, and professionals better understand the wide range of everyday demands children face—both obvious and hidden. The checklist highlights how demands show up across home, school, social, and transition times, offering a clearer picture of what might be contributing to a child’s overwhelm or distress.

📖 Books

- Declarative Language Handbook by Linda K. Murphy

- Low-Demand Parenting by Amanda Diekman

🎧 Webinars

- PDA Aware Preschools – coming soon!

An insightful webinar designed to help educators and parents understand and support PDA in preschool settings. Sign up to our newsletter to get access when it’s live.

Dr Nicole Carvill is a respected child psychologist, presenter, researcher and PhD graduate who specialises in supporting neurodivergent children and their families. As the founder of Think Psychologists, she brings warmth, insight and a strong commitment to evidence-informed care. Nicole regularly presents to parents, educators and clinicians on topics including emotional regulation, inclusive education and trauma-informed practice.

Disclaimer:

The information provided in this blog is for general educational and informational purposes only and is not intended as a substitute for professional advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Every child and situation is unique. If you have concerns about your child’s mental health, behaviour, or wellbeing, please seek advice from our team or a qualified health professional. Engaging with this content does not replace personalised support from a healthcare professional.